What drives changes in real GDP per capita?

Economists often use the trend in real GDP per capita as a rough proxy for the trend in overall welfare. If this ratio is rising Canadians, in general, are probably getting better off. It is an incomplete measure of welfare, but in the absence of some other readily available and timely overall indicator, real GDP per capita continues to rule the roost.12

GDP per capita plunged as the pandemic took hold and while it rebounded fairly quickly, edging above its 2019 Q4 level in 2022 Q2, in recent quarters the ratio turned back down, a matter of concern to many economists. This paper explores factors that go some distance in explaining what has been happening to the ratio lately. Its focus is on the period starting in 2020, although some comments are also offered on longer-term trends.

The progress of real GDP per capita since 1997

Chart 1 plots the course of Canada’s real GDP per capita on a seasonally adjusted basis since the first quarter of 1997. It peaked in the third quarter of 2008 after a lengthy period of growth, increasing at a 2.1% compound annual average rate from the first quarter of 1997 forward3. It then dropped 5.5% over a four-quarter period during the ‘great recession’. Thereafter it resumed its upward climb to the first quarter of 2020, although rising at only a 1.3% compound annual average rate. Finally, during the following 13 pandemic-affected quarters it first plunged, when the mandatory economic shutdowns began in the second quarter of 2020, and then began a gradual recovery in the third quarter as better ways of coping with the virus were implemented.4

By the second quarter of 2023 though, as noted, real GDP per capita was again below its pre-pandemic value and indeed seemed to be trending back down.

What are the drivers of real GDP per capita?

One can hypothesize a number of factors influencing the growth of real GDP per capita over time. Increased literacy, for example, has been shown to be an important one.5 Capital accumulation is another. These and a number of other causal factors are also determinants of labour productivity growth, which be a major focus here. Some other variables affecting GDP per capita include average hours worked per employee, the overall employment rate, the age structure of the population and the relative growth of the business sector.

This paper explores five specific factors that may be contributing to recent changes in GDP per capita, which are:

Declining business sector labour productivity,6

Decreasing average hours worked per job,

Slowing growth of employment relative to the working-age population,

Demographic aging and

The growth of private business GDP relative to total GDP.

These factors are measured using indexes, scaled to 2012 = 100. This is also the practice followed by Statistics Canada in its table 36-10-0206-01, from which these time series are drawn. With these indexes we are analyzing determinants of relative changes in real GDP per capita, rather the level of real GDP per capita.7

A decomposition of real GDP per capita

The factors just mentioned are examined by means of the following decomposition of real GDP per capita. It is a simple multiplicative identity.8 For this purpose we define the following time series variables:

GDP = real all-industries gross domestic product at basic prices (in Statistics Canada table 36-10-0434-01)

POP = total Canadian population (in Statistics Canada table 17-10-0009-01)

BGDP = real business sector gross domestic product at basic prices (in Statistics Canada table 36-10-0206-01)

HOURS = total business sector hours worked (in Statistics Canada table 36-10-0206-01)

JOBS = total business sector employee jobs, working owners of unincorporated businesses, own account self-employed and unpaid family jobs (in Statistics Canada table 36-10-0206-01)

WPOP = Canadian population of persons aged 15 to 65 (in Statistics Canada table 14-10-0287-01)

AHRS = average hours worked per business sector job (in Statistics Canada table 36-10-0206-01)

These variables allow us to specify the following identity:

(1) GDP/POP = BGDP/HOURS * AHRS * JOBS/WPOP * WPOP/POP * GDP/BGDP

where HOURS = AHRS * JOBS

In words, the equation says that total real GDP per capita is equal to business sector labour productivity (GDP divided by hours worked), times average hours worked per job in the business sector, times the ratio of the number of business sector jobs to the working age population, times the share of the working age population in the total population, times the ratio of total real GDP to business sector GDP.

The six time series

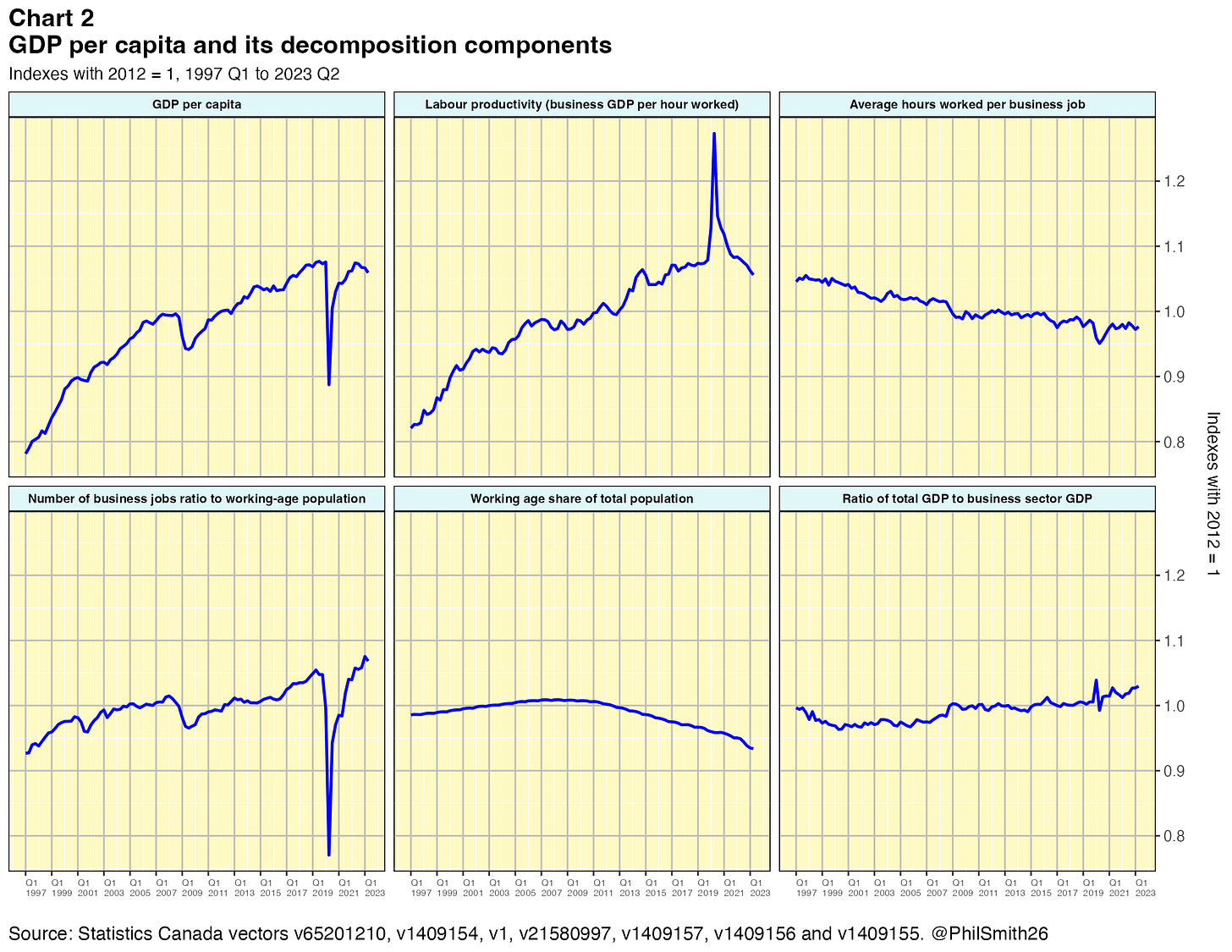

Chart 2 shows the time series evolution of the six variables in equation (1), all plotted to the same scale.9 The first one, GDP per capita, was discussed previously. Of the other five, labour productivity’s relative change over the 25-year period has been much greater than the others. It is clearly the main driver of GDP per capita in the long run.

Labour productivity has a good correlation with GDP per capita. One difference though is in the ‘great recession’ when GDP per capita dropped substantially while labour productivity just levelled off. The other major difference is at the start of the pandemic period in 2020 when GDP plunged while labour productivity soared. This was a temporary phenomenon caused by sharp compositional shifts in employment and in subsequent quarters the composition gradually returned to normal.10 However, by the second quarter of 2023 labour productivity was still on a decline. Changes in labour productivity are attributable to changes in multi-factor productivity, labour quality and capital intensity.11

Average hours worked per business job, in the third plot, show a downward trend over much of the period. If employees work fewer hours per production period than previously, whether for personal or employer preference reasons, this will clearly tend to reduce GDP per capita. If effect, society is choosing to take some of the benefits of economic progress in the form of more leisure time, rather than as purchased goods and services.12 Hours worked did stabilize for a while, between 2009 and 2015, before resuming their downward trend. They also decreased substantially, and temporarily, at the start of the pandemic as employers adapted to reduced consumer demand and mandatory production limits.

The number of business jobs, expressed as a ratio to the working-age population, shows the inclination and capacity of prime-age Canadians to take employment. The higher this labour market engagement rate, the higher GDP per capita will tend to be. The ratio trended up between 1997 and 2008, fell during the ‘great recession’ and resumed the upward trend thereafter. It plummeted at the start of the pandemic and this of course was the major factor explaining why GDP per capita dropped as well. It then began a quarter-by-quarter rebound, finally exceeding its pre-pandemic level in the second quarter of 2022.

The working-age share of the population is another important determinant of GDP per capita. It has been on a substantial declining trend since around 2011. This demographic change — the aging of the Canadian population — has been under way for some time. The shift in the ratio began as the baby boom generation began to move into retirement. So while the total population has continued to grow, the share of persons aged in the most productive working years has been shrinking.13

The final ratio, total real GDP to business sector GDP, is needed to complete the identity. The difference between the numerator and denominator includes the real gross value added of the public administration, health care and education industries and of the non-profit institutions serving households sector, plus the imputed rental value of owner-occupied dwellings. All of these components except for the non-profits kept growing during the ‘great recession’ while business sector output decreased and was slow to recover in 2009 and 2010. Thus the ratio increased in late 2008 and early 2009 and remained fairly stable around this higher level until the pandemic struck in 2020. After the extreme volatility in the first half of 2020, the ratio moved again to a higher level. Since the pandemic began in March 2020, total real GDP rose 3.8%, business sector GDP 2.8%, public administration GDP 8.3%, health and social welfare GDP 7.9%, education GDP 6.4%, non-profit institutions 7.3% and imputed rent 9.0%. In other words, one might say that the growth of total real GDP per capita has been somewhat ‘propped up’ since the pandemic began by disproportionately strong growth in the non-business sector.14

Logarithmic changes

The quarterly change in a logarithmic time series is equal, to a close approximation, to the quarterly percentage change. Equation (2), derived from equation (1), shows the logarithmic change in real GDP per capita expressed as the sum of the logarithmic changes in the five previously discussed factors.

(2) Δln(GDP/POP) = Δln(BGDP/HOURS) + Δln(AHRS) + Δln(JOBS/WPOP) + Δln(WPOP/POP) + Δln(GDP/BGDP)

Applying this decomposition over the period between 2019 Q1 and 2023 Q2 yields the results in table 1.

The table shows that as the pandemic was beginning, real GDP per capita increased marginally in 2020 Q1 and then plunged 19.2% in 2020 Q2. The huge decrease was attributable to the 25.7% drop in the number of business jobs as a ratio to the working age population, although average hours worked per job, the working-age share of the population and the inverse of the business sector share in total GDP also fell. Labour productivity was the outlier in the second quarter, rising 12.1% due to the compositional shift away from low-skilled and less experienced employees which were disproportionately laid off due to lower consumer demand combined with government-imposed pandemic restrictions. The fall of GDP per capita in the second quarter was then partially reversed in the third quarter, as it rose 12.4%. Again labour productivity was the outlier, dropping 10.5% while the other drivers, especially jobs, accounted for the rebound. This recovery pattern generally continued through to the second half of 2022 with GDP per capita coming back up, driven largely by rising jobs and average hours worked, while labour productivity continued to decrease.

The most recent four quarters, between 2022 Q3 and 2023 Q2, broke this pattern. GDP per capita and labour productivity both decreased. The other important factor for these most recent quarters was the working-age population share in the total population, which dropped a lot more rapidly than in previous quarters.

Cumulative logarithmic change

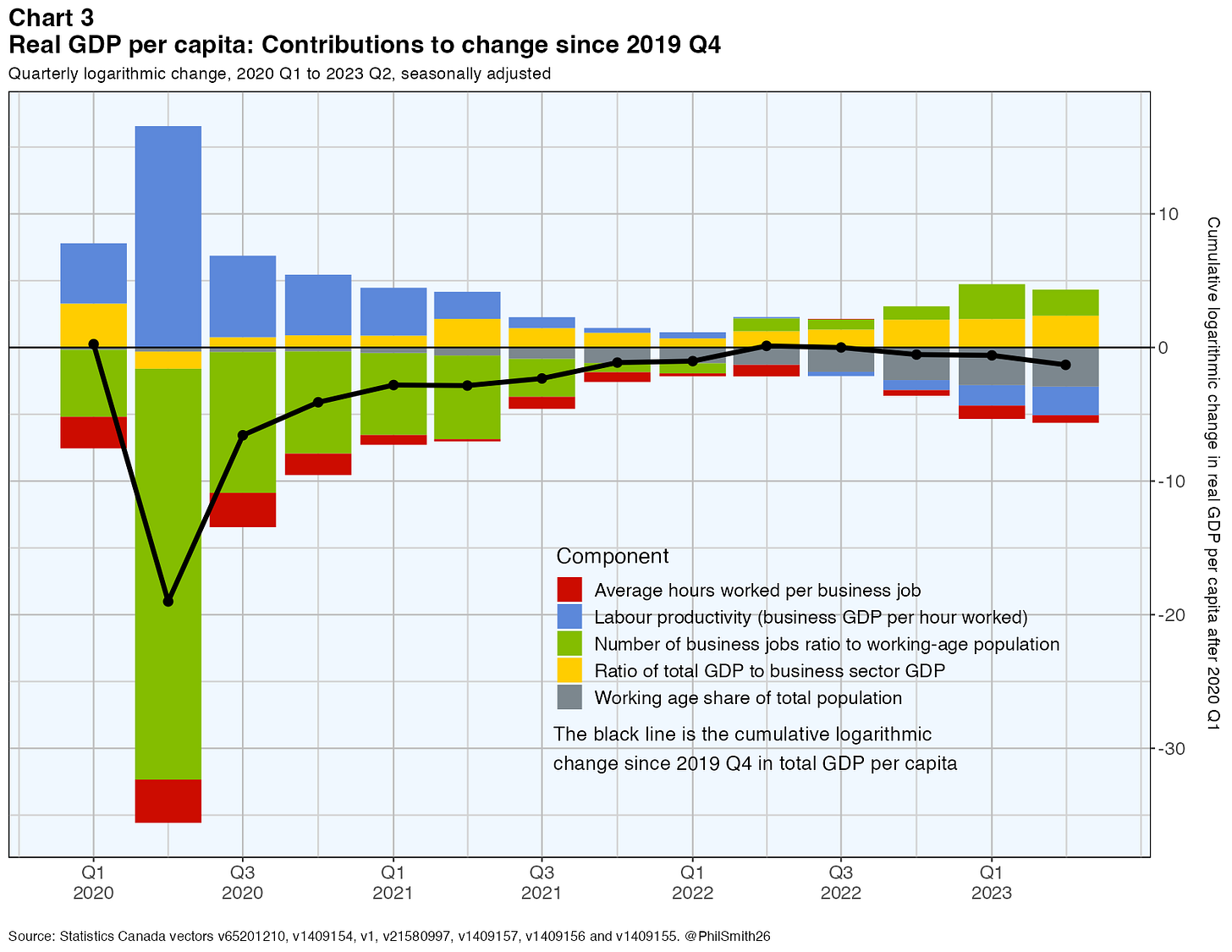

Chart 3 shows the cumulative logarithmic change in GDP per capita and the five identified factors that are driving it. The cumulative changes in GDP per capita are shown as a black line and the factors are displayed as coloured bars that add up to the changes in GDP per capita. The statistics shown in this chart are the cumulated numbers from table 1.

From the black line it is evident that GDP per capita, after nosediving in 2020 Q2, did not return to its pre-pandemic level until 2022 Q2. After that point, no further upward progress was recorded and indeed the ratio edged down a bit.

As of the second quarter of this year, it is the cumulative decline in the working-age population share that has been the main factor accounting for the weakness in real GDP per capita. The cumulative decline in labour productivity is another key factor and declining average hours worked per job is also contributing. Serving to moderate these effects on GDP per capita were strong cumulative growth in business sector jobs per working-age Canadian and also growth in non-business sector output relative to business sector output.

Conclusion

The inference from the above analysis is that while yes, weakness in labour productivity in recent quarters is an important explanatory factor behind the lack of growth in real GDP per capita over the last three years, the most important factor right now is the ongoing decline of the working-age population share as baby-boomers retire.

The birth rate was extraordinarily high in 1957 and while it began to decrease after that, the rate remained unusually high for the next ten years or so. Those born back then will be sustaining today’s retirement surge for several years to come. At the other end of the population age distribution, the big increases seen recently in the number of non-permanent residents might begin to provide a partial offset, increasing the working-age population, but since much of this consists of temporary workers, students and refugees, this may not provide much of an offset. This additional labour is likely to have much lower average productivity than the more experienced retirees who are leaving the labour force. Moreover, the availability of this recent surge in low-wage labour supply within Canada may be inducing some businesses to substitute labour for capital, thereby disincentivizing investment in machinery and equipment and dampening labour productivity growth via that channel.

The trend toward lower average hours worked per job may or may not continue, but if it does it is not something to be concerned about. If Canadians prefer to take some of the dividend they receive as a result of a stronger economy in the former of increased leisure time rather than as more market-based goods and services, there is nothing wrong with that.

As for labour productivity, this factor must surely be the main driver of improvements in real GDP per capita in the longer term. Canada’s productivity growth in the decade prior to the pandemic was weak and we must aim for a better performance in the post-pandemic world. The labour composition distortions that made it difficult to understand what was happening with labour productivity during the pandemic and its aftermath have mostly worked themselves out by now, so we should be able to take the productivity results for calendar year 2023 at their face value. Let us hope labour productivity growth starts to increase in the second half of the year.15

Annex: Real GDP per capita versus real GNI per capita

While this article focusses on real GDP per capita, real GNI per capita is a better indicator of Canadian welfare as argued in footnote 2. Chart A1 compares the growth of the latter measure to that of the former over the last 62 years.

Real GNI per capita grew at a 2.4% compound annual average rate between 1961 and 2001 while real GDP per capita increased at a 2.3% rate. That’s hardly any difference. After 2001, however, GNI per capita grew more rapidly, albeit with strong cyclical swings, compared to GDP per capita. This reflected, to a large extent, big changes in Canada’s terms of trade. Canada benefitted from higher global prices for energy products and other raw materials over the last two decades, although this advantage disappeared during the ‘great recession’ in 2008-2009 and again during the ‘mini-recession’ of 2015-2016. The terms of trade also improved remarkably in the two years following the pandemic shutdowns in early 2020 before weakening again in the most recent few quarters. It is also notable that although Canada was a net debtor to other countries for a long time, in 2014 it became a net lender and the country’s net financial asset position has grown steadily larger since then.

The author wishes to thank Lawrence Schembri and Paul Jacobson for helpful comments and suggestions on an earlier draft. Any remaining deficiencies are, of course, mine alone.

GDP per capita measures an economy’s market income — a very important element in social welfare — but ignores the welfare impact of externalities such as increasing atmospheric, water and land pollution and loss of bio-diversity. It also pays no heed to non-market activities such as household work, volunteer work and the enjoyment of leisure time. The degree of income and wealth inequality is also important, as is the state of a society’s social capital. Also, a good case can be made that for purposes of gauging societal welfare, the use of gross national income (GNI) is preferable to gross domestic product or income (GDP=GDI). While GDP measures domestic production, whether by resident- or non-resident-owned factors of production in Canada, GNI measures the net income accruing to resident-owned factors of production. This means interest and dividends flowing out of Canada to non-residents are subtracted from GDP while interest and dividends earned abroad by Canadian-owned factors of production are added in. Nevertheless this article focusses on GDP, not GNI, since GDP per capita is the centre of the current debate in Canada. The annex to this paper provides a time series comparison of the two.

The year 1997 is chosen as a starting point because that is the initial year in Statistics Canada’s GDP by industry table 36-10-0434-01. The statistics in that table are used again later in this article. It is possible to extend the chart back to the 1920s or earlier, although the real GDP estimates for earlier years are less reliable.

Supplies of good-quality N95 face masks became more readily available, retailers adopted ‘order ahead and wait in your car to pick up your purchase’ and ‘order online for delivery to your door’ protocols, video conferencing became a lot more common, indoor gatherings were limited to just a few people and in 2021 vaccines became available.

For analysis of the impact of improved literacy on GDP per capita see Guido Schwerdt and Simon Wiederhold, “A Macroeconomic Analysis of Literacy and Economic Performance”, February 5, 2019, a paper commissioned by the Programme for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies (PIAAC).

The focus on productivity is limited to the business sector because there are no reliable estimates available for the government and non-profit sectors. The difficulty for the latter is that there are no market prices for most of the sector output. Without market prices for, say, elementary school education or government administration services it is impossible to calculate reliable estimate of real output, the numerator of the productivity calculation. As a result, statisticians typically assume that real output after depreciation is proportional to the real labour input, hours worked, which implies an assumption of constant labour productivity over time. Unfortunately there are no systematic estimates of the productivity of government employees.

Nominal GDP is measured in Canadian dollars and its level has important meaning. Real GDP is an index number, similar to the consumer price index except that instead of measuring changes in prices of heterogeneous products, it measures changes in quantities of heterogeneous products. It is a chained Fisher index, Statistics Canada’s preferred measure. While the index is released by Statistics Canada in ‘chained dollars’, this unit of measure is arbitrary and defies intuitive interpretation. It is only relative changes over time that are being measured by real GDP, not the level.

There are, of course, an infinity of similar identities that could be used, but this one is chosen specifically to shed light on how real GDP per capita relates to the five driving factors mentioned in the text.

The plotted lines in chart 2 are all indexes with 2012 = 1.0 because they are all ratios of pairs of variables that are indexes with 2012 = 100.0.

The years 2020-2022 were extraordinary for the economy. Labour productivity, as conventionally measured, increased very greatly in 2020 and this was due mostly to the changed composition of the workforce, rather than to accelerated employee training or enhancements to the capital services employees work with. Employers disproportionately laid off lesser-skilled and lower-paid employees during the pandemic shutdowns. Then as the rebound got under way the decrease in labour productivity primarily reflected the gradual return toward a more normal composition.

For more on this decomposition of labour productivity, see “Interpreting productivity performance in Canada”, a free paper in my substack archive.

While the longstanding downward trend in average hours worked per job can be taken to imply society is choosing to take some of the benefits of higher productivity in the form of greater leisure time, lower average hours worked per job may also, at times, reflect a shortage of full-time jobs on offer, causing some people to take multiple part-time jobs in order to earn sufficient income. The rapid development of the digital economy has also facilitated some types of self-employment, sometimes called ‘gig’ employment, though it is not clear this causes a reduction in average hours worked per job and indeed may have the opposite effect.

Today’s seniors are generally in better health and more inclined to keep working after age 65 than were those of previous generations. However, their labour force participation rates are a lot lower than those for younger people and their average hours worked also tend to be reduced.

Of course, strong growth in the non-business sector has not ‘propped up’ labour productivity for the total economy, if such a thing were to be calculated, because the labour productivity growth of the non-business sector is essentially zero by assumption.

Finally, the great difficulty of measuring real output growth with good precision must also be kept in mind. While this paper bases its analysis on Statistics Canada’s published estimates, those estimates are subject to unknown statistical biases and error variances. For some products, such as software and high-tech gadgets, quality change is difficult to account for when trying to measure ‘pure price change’ for deflation purposes. Intangible products are seemingly more and more important in today’s digital world and it is often much harder to measure the real output of these products. Increased customization and product diversity add further to the measurement challenge. It is conceivable the recent trend growth of real GDP per capita is substantially stronger than we think. Or weaker.

We should remember that there have been major shifts over the time period shown:

Imports/capita ($K) are more than 5 times higher than 1972. In the 20s, we had the advent of China as manufacturer to the world. This does change domestic productivity,

There has been a major shift to knowledge-based industries with difficult-to-measure output.

An aging population means that an increasing share of GDP is necessarily devoted to public health and social care with value to society not appropriately measured

Another great post, can't thank you enough for sharing your work and knowledge