The state of the Canadian household sector

Coping with higher interest rates and real wage losses due to unanticipated inflation, are households approaching a crisis or are they still in comparatively good shape?

National accounts statisticians like to think of the economy as comprised of five sectors: Households, non-profit institutions, corporations, governments and non-residents. Each receives payments of various kinds from the other sectors and also makes payments to them. For example, corporations receive payments from other sectors that purchase goods and services from them, while making payments to other sectors in the form of wages, interest and dividends. Non-residents receive payments for the products Canada imports, and make payments for the goods and services we export to them. The same goes for the other sectors.

This article is concerned with the state of the households sector. It reviews what has been happening to its income, consumption and saving, its balance sheet and its performance in meeting credit obligations. The paper concludes with a brief assessment of the overall state of the sector.

Overview of the households sector

The households sector accounts for well over half of expenditure-based GDP and as a result, the economic health of the sector is critical for Canada’s overall economic growth. Indeed it can be said that the prosperity of the households sector is the raison d’être of the economic system.

The schematic in chart 1 shows how the sector raised and expended funds in 2022. The main income source was the wage, salary and supplementary income earned by households as compensation for work performed on behalf of employers, amounting to $1,382 billion. Some households also earned net income from unincorporated business activity ($106 billion) and rents ($132 billion). Property income in the form of interest and dividends, amounting to $241 billion, was another important source of funds. In addition to these primary sources of income, households also received transfer payments totalling $424 billion, mostly though not entirely from governments. Employment insurance and old age security benefits are prominent examples. Two additional non-cash types of income are also shown in the chart. The change in pension entitlements ($42 billion) is the accrual of additional benefits households will be entitled to upon retirement and capital consumption allowances ($88 billion) represent the implicit income homeowners receive from their properties during the year. Finally, since households collectively spent more money in 2022 than they raised in the various ways just discussed, the final source of funds shown in the chart is net borrowing of $66 billion from other sectors.

The right-hand-side of chart 1 displays the various ways in which households made use of their funds in 2022. Consumer expenditure of $1,470 billion is by far the largest item. Personal income tax assessments of $344 billion were the second largest outlay category. Households also paid interest (‘property income’) to other sectors, largely mortgage interest, plus some smaller transfers to other sectors. Capital acquisitions, mostly housing, accounted for $244 billion.

Net borrowing and lending

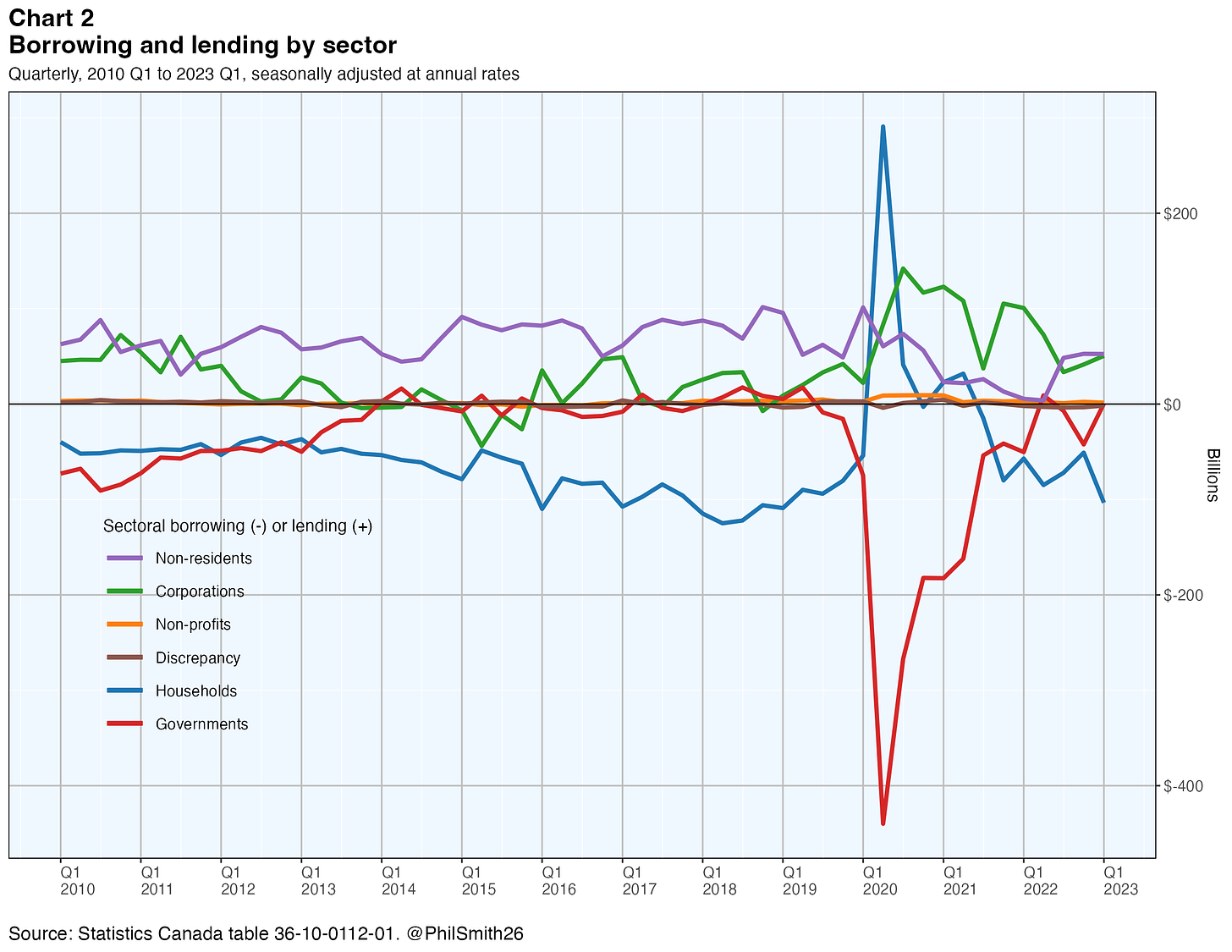

As mentioned, chart 1 shows the $66 billion households borrowed, on a net basis, from other sectors in 2022. In this way of looking at things, borrowing and lending within a sector cancel out.1 The various sectors all borrow from or lend to other sectors. When all sectors are consolidated in a single national entity, this activity also must cancel out, if measured accurately.2 But it is quite interesting to observe which individual sectors are net borrowers and which are net lenders.

Chart 2 shows the net borrowing or lending of each sector since 2010. In the case of the household sector (blue) there has been net borrowing, rather than lending, in almost all periods, the exceptions being between 2020 Q2 and 2021 Q2. Household borrowing facilitates the purchase of owner-occupied housing as well as consumer goods and services. During the five quarters just mentioned the sector’s spending was severely constrained by the COVID-19 pandemic restrictions, which put households in the position of being able to lend to other sectors.3 This contrasted greatly with the government sector (red line) which, between 2014 and 2019, borrowed or lent very little on a net basis4 while becoming a huge net borrower during the pandemic. In effect, Canadian governments ‘soaked up’ the funds that households, and also corporations (green), non-profit institutions (orange) and non-residents (purple), were making available during those troubled times and used them to assist those most adversely affected by the economic shutdowns.

Since the final quarter of 2021, Canadian household net borrowing has returned to a level that is quite similar to what it was before the pandemic. This might be taken as one sign that households’ general economic situation is largely ‘back to normal’. There are of course other signals that may or may not be so positive.

Household disposable income

Household expenditures, of course, are driven by the sector’s disposable income, the major components of which, from chart 1, are shown again in chart 3, this time as they have evolved through time.

Compensation of employees

Compensation of employees (purple in chart 3) tends to grow fairly steadily, as employment and average compensation per employee rise through time. The category did drop in the first full pandemic quarter, when the shutdowns came, but total employee compensation has recovered at a good pace since then, reflecting strong employment recovery coupled with percentage increases in average earnings well above those before the pandemic.

But the latter part of the statement is in some ways misleading. Chart 4 shows indexes of total compensation of employees, the total number of employees, average compensation and real (inflation-adjusted) average compensation. Over the period since the fourth quarter of 2019, total compensation of employees rose 20.3%. This was comprised of 6.3% growth in the number of employees and a 13.2% advance in average compensation per employee. But consumer prices also increased 13.2% so in inflation-adjusted terms, average compensation came out of this extraordinary three-year period unchanged.5 So in terms of their employment compensation, employees collectively were, in early 2023, no worse off and no better off than they were before the pandemic began.6

Non-wage income components

Compensation of employees accounts for about 60% of pre-tax household income and the remainder is unincorporated business income (11%), interest and dividends received (11%) and social benefits and other transfers received (18%). The evolution of these non-wage shares of income is shown in chart 5.

The largest of these is social benefits and other transfers received. Its share rose in 2016 when the federal government introduced the child benefit7 and then it shot up dramatically in early 2020 in response to the temporary COVID-19 shutdowns, when so many people lost their usual sources of income. The shares of unincorporated business income and interest and dividends received were fairly stable until the pandemic when they fell as the Bank of Canada cut its policy interest rate to near zero. They rose again starting in 2022 when the economy was strengthening and the Bank reversed that policy to fight rising inflation.

Chart 6 shows the deductions from pre-tax income that bring us to household disposable income. The main ones are personal income tax and other transfers, the latter including employment insurance contributions among other transfers. Interest paid by households to other sectors is the remaining deduction which, like interest and dividends received as seen in chart 5, dropped initially when the pandemic began but began rising in 2022 when the Bank of Canada adopted a restrictive monetary policy. Interest payments as a share of pre-tax income are currently higher than at any time in the past quarter century, at 5%. The share’s maximum since 1961, when the time series begins, was 7.8% in mid 1981.

Distribution of household disposable income

Growth in household disposable income is highly consequential, especially in an inflationary environment. But the distribution of income among households is also important. Canada has never left this distribution entirely in the hands of the market economy. Rather it has adopted a variety of policies, such as the progressive income tax and targeted social assistance transfers, aimed at making the distribution more equal.

Chart 7 shows how the distribution of income has evolved over the last 24 years. It is generally slow to change, but there have been some notable shifts in recent years in the direction of a more equal distribution. The lowest, second and third quintiles have each received larger shares while the fourth quintile has experienced small declines in the last two years and the highest income quintile has seen substantial decreases in its share beginning around 2008 and continuing.

These changes in the distribution of after-tax income imply that the households least able to cope with rising interest rates and inflation, housing shortages and other economic stresses are, at least in a better relative position.

Household saving

Household saving is defined as the difference between household disposable income and household consumption expenditures, plus the change in pension entitlements.8 The latter is a non-cash component of income representing the amount by which the pension entitlements of households have risen, during a period of time, as part of their employment compensation. It is small in relation to household disposable income, just 2.7% in the first quarter of 2023, in part because fewer than 40% of employed Canadians receive a pension benefit from their employers.9

Chart 8 gives a six-decade perspective on the saving rate (saving as a percentage of disposable income). Not surprisingly, interest rates and inflation are positively correlated with the saving rate because higher interest rates provide a greater reward for saving and higher inflation implies an erosion of the real value of financial wealth, which necessitates further wealth accumulation in nominal terms if the real value of wealth is to be maintained. Note how the saving rate peaked at over 20% in the early 1980s when inflation was in double digits and mortgage rates were flirting with 20%.

The saving rate was very small before the pandemic, reflecting the very low interest rates and low inflation prevailing the time. It shot up to an unprecedented level in early 2020, primarily because household spending was greatly constrained by the COVID-19-related economic shutdowns. Saving has fallen back considerably since then as the pandemic has eased, but remains above the rate in the immediate pre-pandemic years. Households are flush with accumulated savings from the 2020-2023 period.

The household balance sheet

The household sector is in fairly good financial shape, as shown in table 1. As of the first quarter of this year its net worth was $15.70 trillion. Statistics Canada’s latest estimate for the number of households in Canada, in the year 2022,10 was 16.23 million, implying net worth of the average household was $967,000.

The major household asset categories are:

land underlying dwellings, the market value of which has come down considerably from a year ago after rocketing upward for a time;

dwellings, for which the value continues to rise;

life insurance and pensions;

mutual fund shares;

unlisted shares, reflecting in part the value of unincorporated businesses owned by households; and

Canadian currency and deposits.

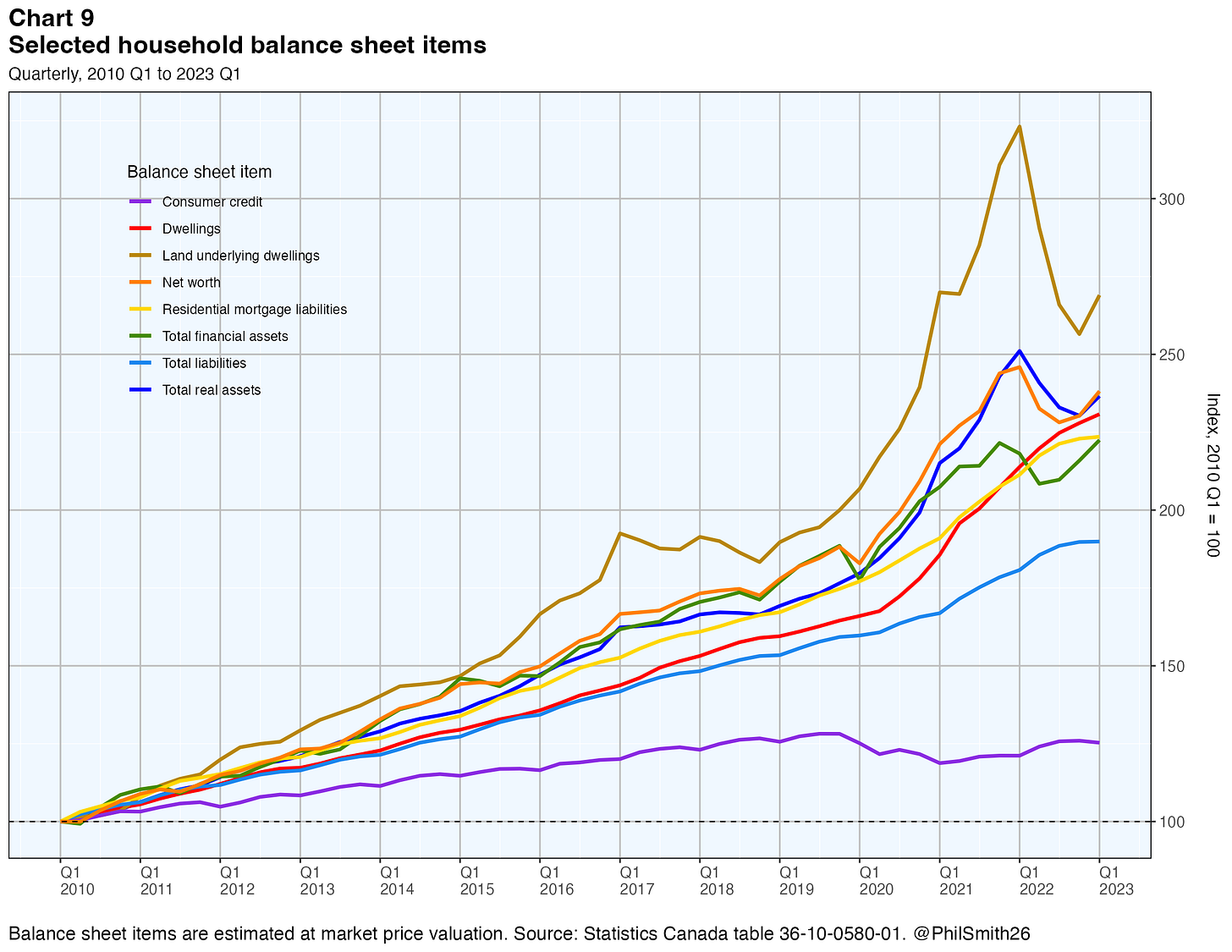

Household liabilities have risen about 5% over the past year as residential mortgage liabilities in particular have increased 5.8%. Nevertheless net financial assets (the difference between financial assets and liabilities) increased 0.7% over the same period, reflecting the higher-the-usual saving rate referred to previously.

Chart 9 shows selected balance sheet entries in a time series context. All of the lines in the chart are indexed to equal 100 in the first quarter of 2010. Land assets under dwellings (brown) stand out for their very big increase since 2010. They did decrease substantially in 2022 but turned up again in the first quarter or 2023. The market value of dwellings (red) has also increased greatly, as have residential mortgage liabilities (yellow). Financial assets (green) declined in late 2021 and early 2022, but turned upward again in mid-year, affected by higher interest rates. Somewhat reassuringly, consumer credit liabilities (purple) have been held tightly in check, a reaction perhaps to higher interest rates and the large accumulated household savings.

Credit performance

A look at recent changes in the balance sheet is one way to explore whether the household sector is approaching a financial crisis point. Another way is to examine credit performance. Rates of arrears on various kinds of consumer loans are shown in chart 10.

Perhaps surprisingly, mortgage loans (blue) is the only category showing no recent pickup in delinquency. This may be due simply to the lags involved when mortgage rates rise, as existing mortgages terms are gradually renewed over time. Credit card arrears (brown) have increased, although not dramatically. Instalment loans (purple) show the largest increase in arrears and this rise has been under way since 2018, possibly due to ongoing restructuring in the financial sector as newer and smaller lending institutions acquire riskier loan assets that the more cautious big banks do not covet.

In sum, while the performance of households in meeting their credit obligations has deteriorated in most categories since mid 2021, this is not surprising given the rise in interest rates and the extent of this deterioration appears to be generally mild so far.

Conclusions

Some Canadian households are certainly less than happy about their current economic situations today than they were not long ago. High housing prices and rising apartment rents in the big metropolitan areas, combined with the increase in mortgage interest rates, are a major source of difficulty for some households. For others, timely health care is becoming harder to find as the country suffers from labour shortages in some professions and inefficiencies in the hospital system. The higher-income quintiles have lost disposable income share and that is usually troubling. On top of all this, forest fires and the associated drifting smoke are currently hurting or at least frightening residents in many areas of the country.

But households always have negatives of some kind to deal with and these must be weighed against the positives. On the plus side, the economic situation of Canadian households is generally quite good as of the spring of 2023. They acquired a lot of financial assets in 2020 and 2021 by saving at a high rate and lending to other sectors. Now their position is back to that of a net borrower, as it had been for many years prior to the pandemic. They are buying houses and taking out mortgages to pay for them despite the higher cost of doing so and the appearance of shortages in some areas. Despite real wage declines in the face of unexpected inflation, average household real incomes in the first quarter of 2023 are about the same as in late 2019 as households have found better jobs in the tight labour market, or taken more than one job, or increased their weekly work hours. Unemployment remains low. Inflation is declining. Now, given the lower inflation rates, there is evidence that real wages are finally starting to increase.

So my conclusion is that for now at least the Canadian household sector is in quite good shape.

If one household borrows from another household, the first incurs a liability and the other acquires a corresponding asset. From the perspective of the sector as a whole, there is no net borrowing or lending.

It would be asking too much to expect sectoral borrowing and lending to be measured without error. There is always error in such aggregate statistics and in this case it is calculated residually as the amount that allows all sectoral borrowing and lending to add up to zero. It is shown in chart 2 as the brown line that is very close to the zero line.

For example, a household is lending to a bank when it makes a deposit, or to a government when it buys its bond.

‘On a net basis’ means the difference between all lending done and all borrowing done. Most households or institutions undertake both gross lending and gross borrowing, but it is the net difference that is being discussed here.

If the reader is curious as to why average compensation increased substantially in the first full quarter of the pandemic and then came down gradually in the following years, it was not because employers quickly jacked up wage rates and then began to reduce them again. Rather, it was a compositional effect. The pandemic shutdowns led to major layoffs, but the people laid off were generally lower-wage employees. Employers expected the shutdowns to be temporary and wanted to retain their higher-wage, more experienced and educated, and more difficult-to-replace employees. As a result, average compensation rose, even if hypothetically no individual employee’s compensation actually increased, and then came back down as the lower-wage employees were eventually rehired.

Mind you it does seem that hourly real wage rates have declined over this period. But employees managed to keep pace with inflation by switching to new jobs with higher pay, taking on multiple jobs and/or working additional hours per week in their main job.

The Canada Child Benefit as it is called provides support to families with children. It replaced several existing programs and was both more generous and better targeted. It has reduced child poverty rates in Canada substantially.

Household saving differs from net borrowing or lending, discussed earlier, because while saving deducts consumption from income, net borrowing or lending also deducts capital spending.

Statistics Canada, “Pension plans in Canada, as of January 1, 2021”, The Daily, July 18, 2022.

The estimate was obtained from Statistics Canada’s table 36-10-0101-01.

Great work