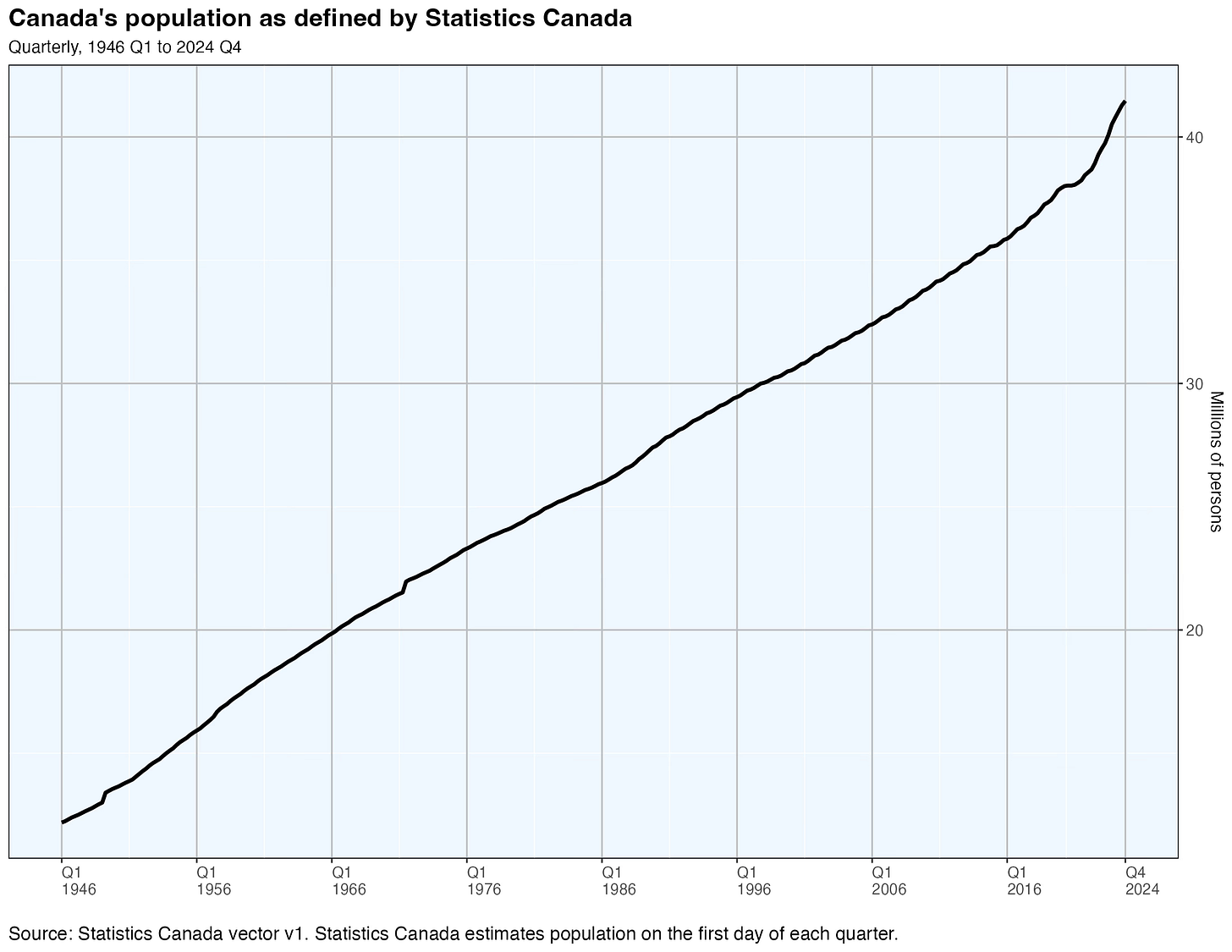

Statistics Canada estimates the size of Canada’s population as 41,465,298 on October 1, 2024. But what does this number mean, exactly?

What is the number?

The number, of course, is not a precise count. It is, rather, a statistical estimate, a calculation based on a number of different sources of information — birth and death records, income tax records and border-crossing records mainly, along with the quinquennial census that was last conducted in 2021.1

The population number for October 1, 2024 was released by Statistics Canada on December 17, in other words 77 days later. It is very much a preliminary number because it draws upon partial and incomplete information. The number will be revised in the quarters and years ahead as more and better information becomes available. The final estimate will arrive some years down the road after the next census is conducted in 2026 and Statistics Canada has had time to compile the resulting data.

Here, as in many other situations, Statistics Canada must address a trade-off between accuracy and timeliness. Both are desired by data users, but timeliness cannot be achieved without some temporary sacrifice in accuracy. Accuracy improves as more information becomes available and the estimates are revised. Of course, the objective is to make the sacrifice as small as possible by exploiting all information sources that can be obtained early on in the process, but revisions are inevitable.

What does the population number mean? SNA perspective

The number is not a statistical estimate of how many living human bodies were physically present within Canada’s borders on that day. There were, certainly, some Canadians who were travelling abroad on that day and yet they were still included in the number. There were also some people living in other countries who were visiting Canada for a week or two as tourists, or to visit friends, relatives or business connections on October 1. They were not included in the number. The number is an estimate of how many people are resident in Canada on that day.

All of which leads to the question: What does ‘resident’ mean? The international System of National Accounts (SNA)2 defines a resident, for its purposes, as follows:

An institutional unit is said to be resident within the economic territory of a country when it maintains a centre of predominant economic interest in that territory, that is, when it engages, or intends to engage, in economic activities or transactions on a significant scale either indefinitely or over a long period of time, usually interpreted as one year.

And what does the term ‘institutional unit’ refer to in this definition? Here is what the SNA 2008 manual has to say on that subject:

Two main kinds of institutional units, or transactors, are distinguished in the SNA; households and legal entities. Legal entities are either entities created for purposes of production, mainly corporations and non-profit institutions (NPIs), or entities created by political processes, specifically government units. The defining characteristic of an institutional unit is that it is capable of owning goods and assets, incurring liabilities and engaging in economic activities and transactions with other units in its own right.

The population is not a count of the number of institutional units in Canada. Rather it is a count of the number of individuals living within one specific kind of institutional unit, the household. Statistics Canada estimates the number of such households as 16,547,214 as of July 1, 20243 which implies the average number of individuals within a household was 2.5 as of that date.4

So coming back to what the term ‘resident’ household means, the SNA says it is one that “maintains a centre of predominant economic interest in [Canada], that is, when it engages, or intends to engage, in economic activities or transactions on a significant scale either indefinitely or over a long period of time, usually interpreted as one year.” People living in a resident household are considered to be part of the population.

This is clear enough as it stands, but how can or should it be operationalized?

Demographic perspective

Statistics Canada’s official estimates of the population, calculated by means of its quinquennial census of population and its intercensal demography program, are defined to include5:

• Canadian citizens (by birth or by naturalization), landed immigrants (permanent residents), and (since 1991) non-permanent residents. Non-permanent residents are persons who have claimed refugee status [asylum claimants, protected persons and members of related groups], or persons who hold a work or study permit and their family members living with them (the census universe also includes people with a usual place of residence in Canada, who hold a temporary resident permit [formerly known as a Minister's Permit], and their family members living with them). All such persons are included in the population provided they have a usual place of residence in Canada.

• The total population also includes certain Canadian citizens and landed immigrants (permanent residents) living outside the country: government employees working outside Canada; embassy staff posted to other countries; members of the Canadian Armed Forces stationed outside Canada; and Canadian crew members of merchant vessels and their families. Together, they are referred to as 'persons living outside Canada.'

• Foreign residents are excluded from census data: for example, residents of another country visiting Canada temporarily, government representatives of another country posted in Canada and members of the armed forces of another country stationed in Canada.

This too seems clear enough and is not obviously inconsistent with the SNA concept of members of resident households. Its distinguishing feature is that unlike the SNA definition, it is fully operational. First, you must have a usual place of residence in Canada. Then if you are a citizen or landed immigrant, you are in the population. If you have filed a claim for refugee status, you are also in the population. And if you hold a work permit or a foreign student permit or are a member of a family with such a permit, you are in the population. By implication, if your refugee application is turned down or if your work or study permit expires, then you are no longer in the population. Unlike the SNA concept of a resident, however, the demography program definition of the population contains no reference to maintaining a centre of predominant economic interest in Canada extending either indefinitely or over a long period of time, usually interpreted as one year.

The demography definition notes that prior to 1991, non-permanent residents (NPRs) were excluded. There is an argument to be made that they should remain excluded. It really depends on the context within which the population concept is to be used. NPRs are producers, consumers and tax-payers just as much as citizens and permanent residents are. Clearly reliable estimates of their numbers and characteristics are important for purposes of economic analysis and policy-making, although this does not necessarily mean their numbers should be included in the definition of “the population”. It can be argued the NPRs should not be taken into account when the focus is on well-being indicators, intergovernmental transfers, major social programs such as Old Age Security and the Child Tax Benefit, and electoral boundaries. The welfare and parliamentary representation of individuals who are here temporarily are not greatly relevant to the well-being of the country.

In this regard it would be beneficial if economic aggregates such as gross domestic product and household consumption expenditure could somehow be split into components attributable separately to NPRs and the rest of the population. This would be no simple task, of course, and would be more of a modelling exercise than simple accounting. But if such a split were available it would then be possible to explore how ratios such as GDP per capita and consumption expenditure per household evolve differently in the two population sub-groups.

Exploring the non-permanency boundaries

As noted, the census definition of the population is an operational one. If you are awaiting a decision on an application for refugee status6 or have a work or study permit and your claim or permit remains active, then you qualify to be included in the population count. Once you lose your refugee claim or your permit expires you no longer qualify. That is implicit. But the latter aspect of the definition raises an issue. People whose refugee claims fail or whose permits expire do not necessarily leave Canada. Some former refugee claimants may stay in the country anyway and it appears the government enforcement mechanisms for detecting and deporting them are not very effective. The official quarterly population estimates assume they do leave within a few months and Statistics Canada has little or no information at present about their actual status until the census of population is conducted. Better intercensal data sources in this area are clearly needed.

If reliable statistics on the number of people here illegally were available, should that number be included in the population or not? That is debatable. Work and study permit holders can apply for permanent resident status when their permits expire and it can take months or even years for these applications to be resolved. Should these people be included in the population count and if so, on what basis since the stated census definition makes no allowance for permanent resident applicants (other than asylum seekers)?7

An intermediary group must be recognized between, on the one hand, the tourist who visits Canada for a week or two and, on the other hand, the citizen or landed immigrant who resides indefinitely in Canada. No one thinks the former should be counted in the population and everyone agrees the latter should be. The intermediary group consists of the following categories:

Asylum applicants, foreign students with study permits and foreign workers with temporary work permits;

Asylum applicants who were turned down, foreign students whose study permits have expired and temporary foreign workers whose permits have expired, who are required to leave Canada but have not done so;

Foreign students and temporary foreign workers whose permits have expired, but who have applied for permanent residency status and are waiting, in Canada, for a decision on their applications;

People who have entered Canada illegally by one means or another;

People who were admitted to Canada legally as tourists, or as persons here to do business, or as temporary visitors here for other reasons and have remained indefinitely.8

Statistics Canada includes group 1 in the formal definition, but seemingly not the others. Group 3 is easily measured via the administrative records of Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada, but Statistics Canada’s formal definition of the population clearly excludes them. Groups 2, 4 and 5 might be excluded from the population concept for purely operational reasons, since data sources are lacking to measure numbers in these groups. If so, it would be helpful if the formal Statistics Canada definition of the population excluded them explicitly.

The role of personal and government intent

The SNA definition of a resident makes use of the word intent when it says: “engages, or intends to engage, in economic activities …”. The notion of intent can, should and does influence thinking about the definition of the word ‘population’ but it should not, in my view, form part of that definition itself. Non-permanent resident status for an individual should not depend on his or her intent — to remain in Canada indefinitely or to return to his or her country of origin within a relatively short period of time. It should not rest on the government’s intent to allow or disallow them either. This is because intent is intangible, sometimes capricious and unmeasurable, although when the government’s intent is embodied in laws and regulations that is quite a different matter. Including “intent” in the definition would make it impractical.

Drawing some conclusions

Personally, I draw the following conclusions from the above discussion.

It is desirable that Statistics Canada’s formal definition of the population align closely with the international SNA concept of ‘resident’. This is important for the internal coherence of Statistics Canada’s overall program and also for international comparability purposes. There should be no need for two different time series, one for the population as estimated in the census and another for the number of residents for SNA purposes. The two concepts do align fairly well already,9 but the SNA definition also requires that a resident “maintains a centre of predominant economic interest in [Canada], that is, [he or she] engages, or intends to engage, in economic activities or transactions on a significant scale either indefinitely or over a long period of time, usually interpreted as one year.” The one-year minimum horizon makes the definition operational. However, the clause “or intends to engage” makes the definition impractical and in my opinion should not be included.

A key question concerns non-permanent residents: which among the five intermediary groups discussed above should be included in, and which should be excluded from the definition of “the population”? This issue is complicated by the fact that for three out of the five intermediary groups the numbers cannot presently be estimated with much accuracy. My suggestion is that the definitional question be dealt with more directly by stating simply that the aim is to include in the population all NPRs who have resided in Canada for a year or more. The quinquennial census of population would of course continue to be central to estimating this definition of the population. Personal income tax records would also be valuable when implementing this suggestion, as at present, although of course not everyone files an income tax return. This would mean that foreign students studying in Canada for less than a full year and temporary foreign workers present here for just a few months would not be counted in the population. They would be viewed as non-residents and their purchases of goods and services would be treated as exports.

Regardless of whether some or all of the five intermediary groups are or are not included in the definition of “the population”, Statistics Canada should exert its best efforts to estimate their numbers and publish timely statistics about them. While the numbers in these groups used to be relatively small, that is no longer the case, so analysts and policy-makers need reliable information about all of them. Ideally those statistics should include income estimates for the NPRs, as well as age, sex, residence location and labour-force-related information.

Statistics Canada’s methodology and sources for the population estimates are described in the publication Population and Family Estimation Methods at Statistics Canada, 91-528-X, released March 3, 2016.

System of National Accounts 2008, published jointly by the United Nations, the International Monetary Fund, the Word Bank, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development and the European Commission in New York, 2009.

Statistics Canada table 17-10-0159-01.

The population, found in Statistics Canada table 17-10-0009-01, was 41,288,599 on July 1, 2024. It is notable that the average number of individuals in a household has been declining for decades as more and more people have decided to live in one-person households.

Taken from Statistics Canada’s Quarterly Demography Estimates program description.

The processing time for refugee applications varies greatly depending on a variety of circumstances, but can be as much as four years. The government provides information on the processing lags at this URL.

Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada introduced a policy in August 2020 to help visitors who were unable to leave the country due to COVID-19 pandemic–related travel restrictions. Under the policy, visitors in Canada could apply for a work permit without having to leave the country. In addition, foreign nationals who had held a work permit in the previous 12 months but who changed their status in Canada to “visitor” could apply to work legally in Canada while waiting for a decision on their new work permit application. This policy was formally ended on August 28, 2024.

Some draft-dodging Americans might have fallen into this category during the US-Vietnam war in the 1960s and early 1970s, although Canadian immigration policies at the time were generally open to them remaining in this country while the war went on.

One area where the two concepts diverge is that of trade in travel services, as revealed in this sentence: “International student spending in Canada is therefore an export of services from Canada, often referred to as education-related travel services exports.” (In Revisions to 2022 and 2023 exports of travel services, Statistics Canada catalogue no. 13-605-X, November 12, 2024.) This implies the foreign students are non-residents, whereas in Statistics Canada’s formal definition of the population they are treated as Canadians.

Part 2 (Was not aware of word limit for Comments until sent)

Considerations:

1. Your comments on refugees apply to all expired visa holders.

2. Different components of Statistics Canada as well as Immigration Canada, have information on "actual status", in IRCCs case even addresses of expired visa holders with outstanding visa applications living in Canada. Statistics Canada research on visa student earnings through tax records reveals a much higher share of participation in the student visa holders in the work force. Evidence that a material number of expired student visa holders receive T slips for their pay, have deductions remitted to CRA, and are eligible to file a T1 Income Tax claim and receive a refund.

3. Up to July 1, 2021 official population estimates assumed all expired visa holders left the country within 30 days of the expiry of their visa. Upwards of 1 million temporary visas (plus) expired between the closer of international borders (across the globe) in the Spring of 2020 though to July 1, 2021. During much of 2020, departing Canada was next of impossible. Entering the country of origin of many visa holders was prohibited or restricted well after Canada's borders opened. IRCC made accommodation through blanked extensions. These were not reflected in Statistics Canada demographic data.

Statistics Canada made no adjustments to their methodology during this period. Only for population recorded after July 1, 2021 was the assumed departure period adjusted to (up to)120 days after expiry. However, the expired visa holders who remained through COVID, were removed from the data 30 days after visa expiry. Upwards of one year later (or more) after the IRCC blanket extensions (circulated through IRCC website), some returned to the count upon receipt of standard issue extensions or new temporary visas.

Many (likely hundreds of thousands) let their visas expire while awaiting permanent residency (some received years later, some others permanent residency never came), while continuing to work. Many receiving accolades as "essential workers" during COVID.

The distortions in Demographic data during COVID restrictions are profound with long-lasting implications for demographic counts and projections today. In sum, the official population undercount grew exponentially as a result.

IRCC and Statistics Canada did not collaborate on clarifying "actual status", and Statistics Canada chose not to backdate its adjustments (made in 2023) to extend the expiry cut off from 30 to 120 days after expiry, prior to July 1, 2021.

With the passage of time, and access to IRCC, CRA, and CBSA data, a restating of that population during the COVID period is possible.

In determining who should be included in the official population, your references to the International System of National Accounts (SNA) language are key to what changes are needed.

The SNA definition of a resident is one who engages... in economic activity". Receiving a T slip from ones employer along with having deductions from employment (therefore eligible for inclusion in SEPH data) is proof of engagement. Further, as you cite in your paper;

SNA definition also requires that a resident “maintains a centre of predominant economic interest in [Canada], that is, [he or she] engages, or intends to engage, in economic activities or transactions on a significant scale either indefinitely or over a long period of time, usually interpreted as one year.”

This definition would also support the inclusion of expired visa holders that register with a settlement agency for accommodation, or signs a lease with a private landlord.

I fully agree that "NPR status for an individual should not depend on his or her intent", but signing a lease is an indicator of economic activity of significant scale and economic activity over a long period of time.

I suggest your observation that "Statistics Canada has little or no information at present about their actual status until the census is conducted" needs a revisit. Statistics Canada has access to IRCC, and CBSA data now. They cannot complete their Demographic population series without accessing IRCC data. Statistics Canada researchers are examining visa student incomes using CRA Income tax data. Is Demography Division prohibited the same access?

I am sure Statistics Canada Demography will raise both cost and complexity as barriers to adjusting the definition. However, technology and new information sharing with the CBSA, and perhaps even within Statistics Canada, are key to getting, applying, and sharing better data.

Users require a better and more transparent presentation in order to plan, plan housing, infrastructure, and services. As for international comparability, data requirements change and other nations are recognize need to change as well. Recent changes in U.S. Census data releases, which I will link in separate comments, point to adjustments in U.S. counts, which have historically undercounted asylum seekers compared to the Canadian practice.

I look forward to your thoughts?

Thanks for those patient enough to read though the complete message.

Henry

Henry Lotin

Principal

Integrative Trade and Economics

I should add that another way of working without legal status and paying taxes is with a false NAS. This, it seems, is fairly common for undocumented immigrants in the US. I have no recent information on false NAS in Canada. The Auditor General has been on the government’s case on this matter since 1998.